Yasmin Alibhai-Brown suspected trouble was brewing when her teenage daughter grew testy on the evening of Nov. 10. As Alibhai-Brown recounted to the BBC: “She was incredibly distressed before she went to bed and said, ‘Why do you have to be a journalist, mum? Every time you open the door I think somebody is going to shoot you.'” It was only after a family friend directed Alibhai-Brown to a post on Twitter that she understood her daughter’s concern: someone in the Twittersphere seemed to want her dead.

Earlier that morning Alibhai-Brown, 60, a columnist with London’s Independent newspaper, had appeared on radio and questioned whether any British politician was morally qualified to comment on human-rights abuses, including the stoning of women. That prompted Gareth Compton, a Conservative city councilor in Birmingham, to post the following message on his Twitter account: “Can someone please stone Yasmin Alibhai-Brown to death? I shan’t tell Amnesty if you don’t. It would be a blessing, really.”

Speaking to reporters the following day, Alibhai-Brown compared those comments to “incitement to murder” and suggested they could be racially motivated, as she is a Muslim of Indian descent. Compton, 38, removed the message, posted an apology for his “ill-conceived attempt at humor” and defended himself by saying that Twitter was a forum for “glib comment.” Police didn’t get the joke: they arrested him for violating the Communications Act of 2003 on suspicion of sending an offensive or indecent message and released him on bail pending further investigation. The Conservative Party added to the chorus of hisses by suspending Compton until that investigation is complete.

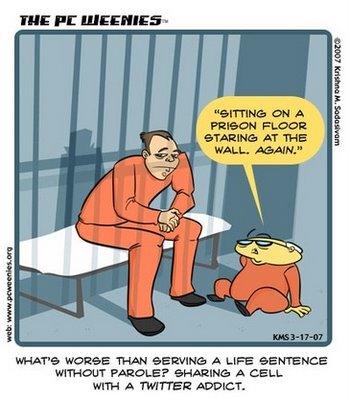

In the freewheeling world of social media, away from societal rules of the real world, people have a different understanding of what should be kept to themselves and what should be shared with those around them — and those all over the globe. As more and more people turn to public forums like Twitter and Facebook to air their private thoughts, the line between appropriate and inappropriate, between a gentle jab and an all-out assault, is still precariously fuzzy — and more people find themselves stumbling as they try to navigate the boundaries. “With these new platforms it takes a while for people to understand how to conduct conversation,” says Charlie Beckett, director of POLIS, the media think tank at the London School of Economics. “People aren’t used to being broadcast all the time. There is a learning curve for all of us.”

And that includes the law. Beckett believes the legal system “is being made an ass” by ignoring the frequently flippant context of Twitter. “Compton is not some racist thug who was trying to conspire for violence against Yasmin Alibhai-Brown,” he says. “It was a stupid remark and that was relatively clear in the tweet. The idea that the courts should now proceed against him is quite ridiculous and disproportionate.” Besides, social media, which is driven by users’ posts and comments — and often their disgust and anger — has a way of policing itself. Thanks to his comment, Compton’s career as a public figure is likely over, and he’s now the target of Twitterers’ wrath. As @grpartington writes: “Yeah bet he’s not feeling quite so smug now the stuck up git! :)”

Regardless of where people stand on the legal action, it’s hard to argue that Compton’s comment wasn’t offensive. But in the case of accountant Paul Chambers, 27, who’s facing legal action for a joke he posted on Twitter, prosecution seems slightly more preposterous.

In January, Chambers was courting a woman who followed him on Twitter and the two had arranged to meet in Ireland. When snow threatened to cancel Chambers’ flight from Doncaster’s Robin Hood Airport, he composed a tweet which he claims to have accidentally posted publicly, rather than sending it via a direct (and private) message: “Crap! Robin Hood airport is closed. You’ve got a week and a bit to get your sh_t together otherwise I’m blowing the airport sky high!!”

Officials at the airport got wind of the facetious bomb threat — and Chambers was eventually convicted of being a “menace.” He lost an appeal on Nov. 11, and must now pay a fine of $1,600 and a further $3,200 in legal expenses. Judge Jacqueline Davies insisted that the tweet in question was “menacing in its content and obviously so. It could not be more clear. Any ordinary person reading this would see it in that way and be alarmed.”

Appropriately enough, Chambers’ conviction has spurred a flurry of tweets ridiculing the decision. By 1pm on Nov. 12, “#TwitterJokeTrial” and “Hood Airport” were the second and third-highest terms trending on Twitter in the U.K. David Allen Green, Chambers’ lawyer, helped feed the fury. “The real threat to the life of the nation … comes not from terrorism but from laws such as these,” he tweeted. That comment echoes the sentiments of civil liberties lawyers who worry the ruling has implications for online freedom, pointing out that the Crown Prosecution Service did not invoke bomb-hoax legislation — which demands strong evidence of intent — but instead leveraged a law that was drawn up in the 1930s to reduce prank calls directed at female post-office operators.

“I just can’t understand what the basis is in national security of prosecuting someone for this,” says Beckett of POLIS. “There has to be some sort of link between a law designed to protect our national security and the actual act. Are they going to come arrest me for re-tweeting the message?” If they do, they better have a thick stack of arrest warrants: thousands of Brits have now re-tweeted Chambers’ “menacing” — and expensive — joke.

Read more: http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2031116,00.html#ixzz15CObGGVf

No Replies to "When A Twitter Post Can Land You In Court"